Suzanne is a Professor in The Centre for Inclusive Education (C4IE) and a member of the Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice. Suzanne’s areas of expertise are inclusive education, ethical leadership for inclusive schools, disability and teacher preparation for inclusive schools. She has engaged in research to inform policy and practice in Australian and international education contexts. She has published over 100 journal articles, books, book chapters and research reports. She is currently the Program Director of Program 2: The School Years for The Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC) www.autismcrc.com.au.

Dr Julie Dillon-Wallace is a Senior Lecturer in the QUT School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education (Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice). Her research and teaching interests include inclusive education, maternal well-being and employment, survey design and ethical conduct in education research. Previously, Julie worked as a classroom teacher.

What is inclusive education?

An inclusive approach to education is a universal human right and focuses on all children learning and socialising together at school or in an early childhood education and care program. An inclusive approach acknowledges our shared humanity and respects the diversities that exist in ability, culture, gender, language, class and ethnicity (Carrington et al. 2021). In 2006, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) was published and has since been ratified by over 180 countries. Australia is a party to the CRPD and is required to ensure an inclusive education system at all levels. Article 24, General Comment 4, which followed in 2016, established the authoritative definition of inclusion as:

… a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience. (United Nations, 2016, paragraph 11)

In an inclusive approach drawing on the social model of disability (Oliver, 1996), we do not see difference as a problem, but value and respect all members (children, teachers and parents) of the community. Teaching and the curriculum are learner-focused with a flexible curriculum and pedagogy to meet children’s needs. In an inclusive approach, teachers receive support from specialist teachers and allied health professionals to provide successful learning opportunities and outcomes for all children.

One of the key challenges in supporting educators to move to a more inclusive approach to education is to understand how inclusion is different to special education. Inclusive education requires a change in mindset to acknowledge and respect student diversity, and support an inclusive approach to curriculum that is responsive to the child, rather than have the child ‘fit’ the curriculum.

What does an inclusive approach look like in early childhood?

The Queensland kindergarten learning guideline (QKLG) states that children learn and progress when all partners hold high expectations and promote equity and success for all. Teachers make curriculum decisions that respect and include children’s diverse ways of being and knowing, social and cultural experiences, geographic locations, abilities and needs.

Importance of high teacher expectations

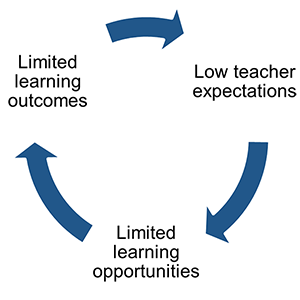

Teacher expectations play an important role in the social, emotional and academic outcomes for young learners. When teachers underestimate student achievement, a self-fulfilling prophecy may occur where inaccurate expectations come true (Brophy, 1983; Cologon, 2014; Jussim & Eccles, 1992). Low teacher expectations lead to a lack of provision of learning opportunities, which in turn affects optimal learning outcomes (Figure 1). This negative cycle further reinforces low teacher expectations.

High teacher expectations can be facilitated and maintained by providing high quality education (Peeters, Lerhoeven & de Moor, 2009). High expectations for all students influence teacher attitudes and practice in fostering appropriate and equitable learning opportunities for young children. High quality early childhood programs provide adjustments for young learners with disability and offer:

- appropriate and flexible curriculum and pedagogy

- interactive learning environments

- age and developmentally appropriate learning resources

- supportive communication modes and technologies (Burns, et al. 2012).

Inclusive schooling pathways espouse the child’s right to engage in equitable learning opportunities and play activities (Cologon, 2014). Inclusive practice is further supported through respectful ways of working, suitable teacher training, ongoing professional development and targeted transition plans to formal schooling (Bryant, 2018). Above all, early childhood teachers and educators need to work hard to break the cycle of low expectations and ensure there are equitable learning opportunities for every child (Cologon, 2014; Zabeli, Gjelaj & Ewing, 2020).

Assessment in the prior-to-school years

High expectations of young learners with disability can be supported by teachers having sufficient knowledge about the young learner. Inclusive strategies and assessments build teacher knowledge and understanding of young learners and should be made across each of the five QKLG learning and development areas: Identity, Connectedness, Wellbeing, Active learning and Communicating.

… aiming to have every young learner work consistently to their highest potential (Cologon, 2014).

Assessment for young children with disability can be challenging due to time constraints. However, assessment should be purposeful and in short form, and gathered in a variety of ways and contexts, thus allowing the learner to demonstrate their strengths, needs and interests.

Data should be analysed, reflected upon, and used to plan and extend the child within their zone of proximal development. Scaffolding provides a bridge from what the child can do on their own to solving a problem or carrying out a task with guidance that is just beyond their current abilities to build new knowledge, skills or dispositions. The ultimate goal is to maintain high teacher expectations and identify the next steps for learning, aiming to have every young learner work consistently to their highest potential (Cologon, 2014).

Collaborative partnerships

It is important that teachers, in collaboration with other professionals working with the same young child, formulate long-term and short-term goals to promote social, emotional and academic progression by way of individualised plans. Both formal and informal assessment can be used to determine the child’s specific learning strengths and needs. In conjunction, it is vital to work with parents/carers, implementing a family-centred approach (PDF, 154 KB). In this way, teachers can consider how the child functions in different environments, gaining insights from individuals who know the child best. The main objective when professionals work together with parents/carers is to ensure that young children are provided meaningful and equitable learning opportunities so they can consistently achieve learning outcomes, and always be working to their highest potential (Cologon, 2014).

Committing to an inclusive approach

Decades of research indicates that inclusive education leads to positive academic and social emotional outcomes for all students, with and without disability (Cologon, 2019; Hehir et al. 2016; Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009; Szumski, Smogorzewska & Karwowski, 2017). All children, including children with disability, have a right to receive an inclusive education. For more information on inclusive education, you can visit the Australian Alliance for Inclusive Education.

An inclusive approach to education in the early years requires teachers and specialists who have experience in disability to work in partnership with parents and carers, guided by early childhood leaders who are committed to equity and inclusion. It is important that teachers, educators and specialists are supported to gain and mobilise the knowledge, inclusive values and teaching approaches to ensure young children with disability are welcomed and supported in inclusive early childhood environments to give them the best possible opportunity to have a good life.

Reflection

- How are high expectations reflected in my program, environments and interactions?

- How do I engage parents and carers as collaborative partners?

- Does my planning and practice include adjustments that allow all children to access and participate in the learning experiences offered?

- Do my assessment methods value the diverse ways children demonstrate what they know and can do?

- How do I make each child’s learning progress visible?

Read more information about inclusion and diversity at:

This article is also available as a PDF.

Reference list

Burns, SM, Johnson, RT & Assaf, MM 2012, Preschool educational in today’s world — Teaching children with diverse backgrounds and abilities, Brooks Publishing Company, ISBN 9781598571950.

Brophy, JE 1983, ‘Research on the self-fulling prophecy and teacher expectations’, Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 75, no. 5, pp. 631–661, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.75.5.631.

Bryant, JP & Ewing, BF (reviewing editor) 2018, ‘A phenomenological study of preschool teachers’ experiences and perspectives on inclusion practices’, Cogent Education, vol. 5, issue 1, pp. 1–12. 10.1080/2331186X.2018.1549005.

Carrington, S & Saggers, B 2021, ‘Moving from a special education model to an inclusive education model: Implications for supporting students on the autism spectrum in inclusive settings — An evidence-based approach’, in Carrington, S, Saggers, B, Harper-Hill, K & Whelan, M 2021, Supporting students on the autism spectrum in inclusive schools: A practical guide to implementing evidence-based approaches. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 3–13, ISBN 9780367501747.

Cologon, K (ed.) 2014, Inclusive Education in the Early Years: Right from the start, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, ISBN 9780195524123.

Cologon, K 2019. ‘Towards inclusive education: A necessary process of transformation’, Children and Young People with Disability Australia, www.cyda.org.au/resources/details/62/towards-inclusive-education-a-necessary-process-of-transformation

Hehir, T, Grindal, T, Freeman, B, Lamoreau, R, Borquaye, Y & Burke, S 2016, A summary of the research evidence on inclusive education. São Paulo: Alana Institute.

Jussim, L & Eccles JS 1992, ‘Teacher expectations II: Construction and reflection of student achievement’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 947–961 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.947.

Oliver, M 1996, Understanding disability: From theory to practice, Red Globe Press, ISBN 9780333599150.

Peeters, M, Verhoeven, L & de Moor, J 2009, ‘Teacher literacy expectation for kindergarten children with cerebral palsy in special education’, International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 251–259, 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32832c0da9.

Ruijs, N & Peetsma, T 2009, ‘Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed’, Educational Research Review, vol. 4, pp. 67–79, 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002.

Szumski, G, Smogorzewska, J & Karwowski, M 2017, ‘Academic achievement of students without special educational needs in inclusive classrooms: A meta-analysis’, Educational Research Review, vol 21, pp.33–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.02.004

UNESCO 2017, A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. Paris.

United Nations 2006, Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. New York, NY.

Zabeli, N, Gjelaj, M & Ewing, B (reviewing editor) 2020, ‘Preschool teachers’ awareness, attitudes and challenges towards inclusive early childhood education: A qualitative study’, Cogent Education,vol. 7, issue 1, pp. 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1791560.